This is happening because we live today in a time of corruption (as well as among corrupt people) and we have to study as hard as possible to avoid corruption, particularly that of our own time, which takes hold of us before we can avoid it, and also that of the past, because we now know all the vices of art and want to protect ourselves against them. We no longer have the simplicity of the Greeks and Romans or the writers of the 14th and 16th centuries, because we have passed through the time of corruption and have become cunning in our art. We avoid those vices with our cunning and our art, not with nature’s help, as the ancients did, who did not know much about them, but who, because art was in its infancy and still not corrupted, neither avoided nor fell into such vices. They were like children who know no vices, we are like old people who know them but avoid them through judgment and experience.

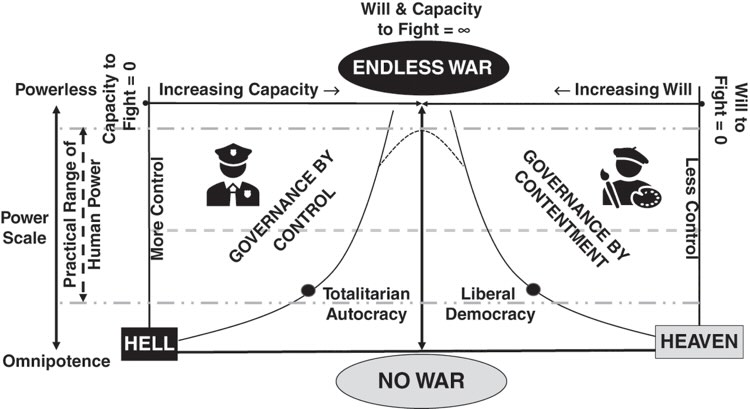

The surest way to rule is to infect others with waiting. This renders them completely harmless and motionless. The deception of waiting is harder than any prison and stronger than any chains. With some luck and skill, one can scale prison walls, but one can never escape from the deception of waiting. Everything you know and are capable of is put in service of this endless waiting, which occurs without hope and without end. Some waste their whole lives, tortured by this aimlessness, while others get everything without waiting at all. Enslaved by waiting, they sometimes give the appearance of resistance, heroic struggles, victories, and new goals and futures. But they merely utter the words that once moved them to action.

Well, here I have to define some words. A primal element is one that comes out of your several million-year-old history as an evolved animal being. Like breathing. All of your direct needs. I think that is one of the things that became so important to me in working for Richard Neutra; all his life he brought his habitants into a direct contact with nature. But a primary experience is like a dot — it’s circumferential, it’s complete with the beginning and end presented at once. It is as intense as something that would take ten years of your life to do. Earlier the three of us watching a couple get out of a red Jaguar and walk into a Japanese restaurant. We remarked it was as if we knew all about them for some time. The three of us had a unanimous and sure response that is unique to us. Maybe there are whole conglommerations of such dots that overlap. So a construction could be a dot like that, which would fall into place in a series of relationships. A series in the sense of overlapping contexts.

HG: Do you perform specific disciplined activities in order to bring yourself to a specific state of mind or awareness? Do you meditate or…

MN: Unless I misunderstand the word meditate, maybe everybody does it constantly by breathing.

HG: Certain artists working in minimal directions have been led to what can be generally considered a religious or transcendent experience in their work and have followed it up with experiments in other disciplines than art. Have you tried to get those feelings through any means except your art?

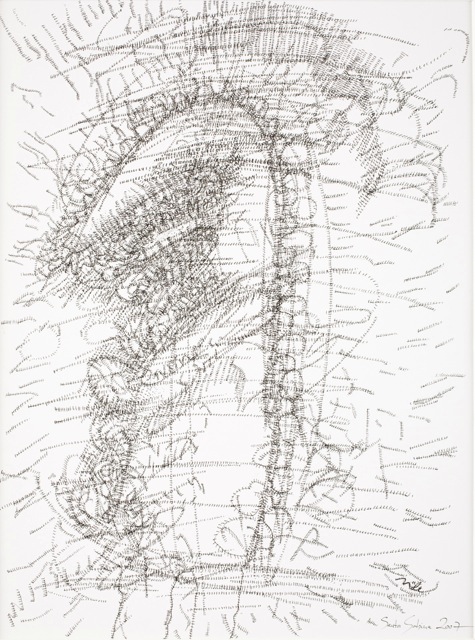

MN: I am working with the maximum, not the minimum. Everything is of consequence whether it is incorporation or removal of feelings. I’ve done lots of different things. Now I go to the ocean a lot. But to answer your question, I see no difference between the constructing and everything else I do. No one has ever told me what meditation is.

CHRONOLOGY

Born 1943 Goerlitz, Silesia, East Germany

1961-1967 University of California at Los Angeles, B.F.A., M.A.

1968 Travel in Europe

Max Planck Institute, Stuttgart, Germany

Collaborative research, coherent light models

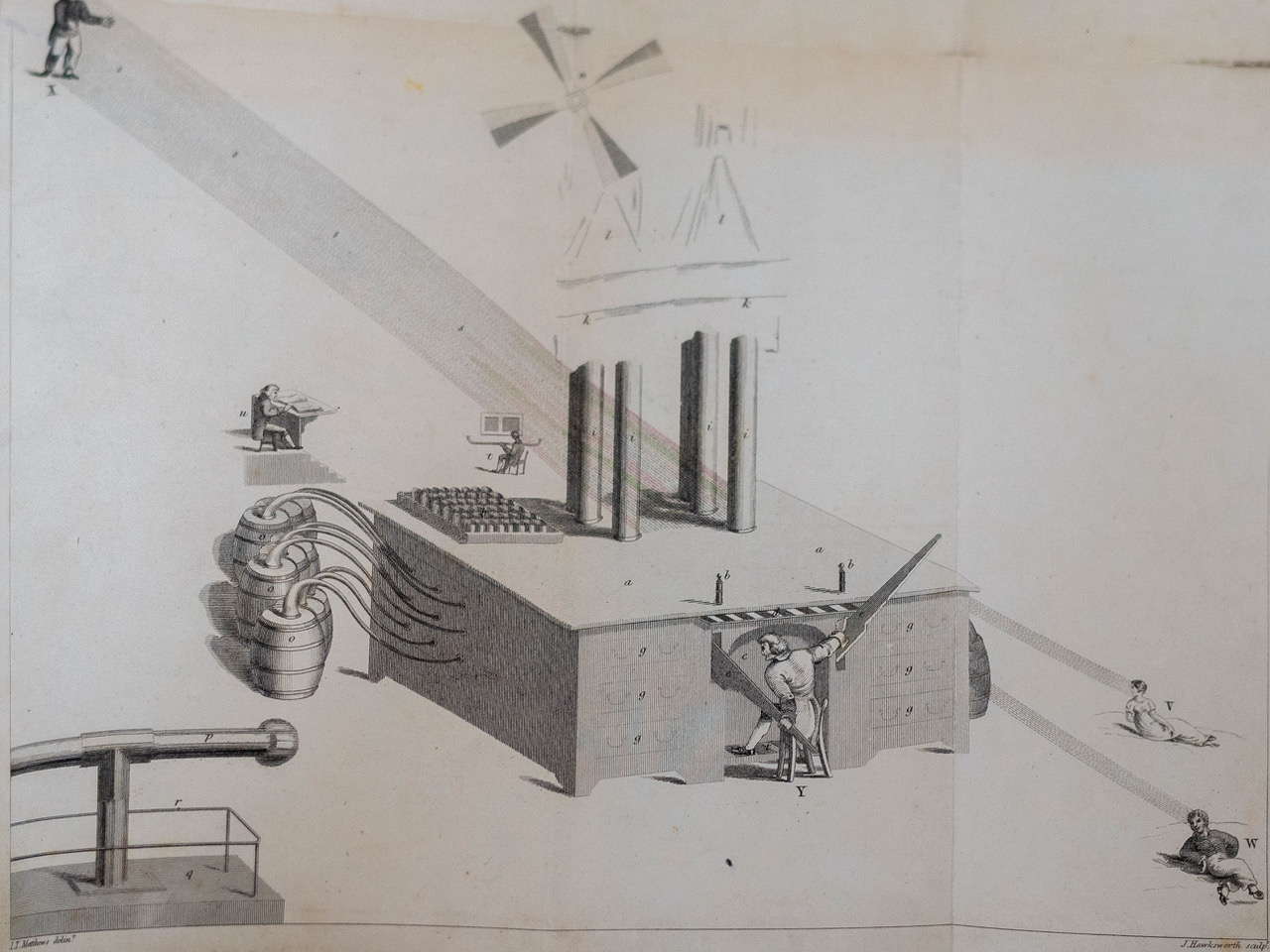

1969-1970 Santa Monica Studio

Room sketch; Coherent light sheets in malleable

environment movable black 8' x 8' walls with light

traversing viewer's space. Maximum size of argon

light: 1/16” thickness x 5’ width x 20’ length

1969-1970 Editorial Assistant to Richard Neutra.

1970-1971 Trona

Light performance; fire, gypsum lake

Amboy

Light performance; fire, trenches and salt.

April, 1971 Santa Monica Studio

30' x 9' white paper hung from ceiling, slowly

curves to flatness of floor. The rest of the room

is black with a 14' ceiling. Natural light forms

two three-dimensional vertical columns that

follow the contour of the paper.

Piece exhibited to public.

November, Santa Monica Studio

1971 14' x 24' parallel walls curve to a point after

16 feet. Space between walls: 28". All surfaces

painted black. Opening of 1/2” lo natural light

from north. At eye level the light produces a

horizontal white plane. Below eye level: voidal

black. Context of street sound.

February, Pasadena Museum of Modern Art

1972 12' x 28' parallel walls with a distance of 28"

between them. Curve to a point after 20 feet.

All surfaces painted black with 1/2” opening to

natural light from north. At eye level the light

produces horizontal white planes of different

focus. Change of piece from vertical to

horizontal. Below eye level: voidal black.

Context of sound: falling water and distant

street.

August, 12 South Raymond Street, Pasadena

1972 16' x 20' black room wiith opening of 1/2” to

sky. The room is divided vertically into a

voidal space to the opening and filling the rest

of the space with a white light. Miniature

for one person.

November, 20th and Idaho, Santa Monica

1972-

January, Sketch of 12’ high x 30' x 20' black room with

1973 vertical opening to east light from entrance

1/4” x 16'. Diagonally connects corner of

rectangular room to entrance producing a

voidal space and a grey prismatic space.

Sound of trees and cars.

February, Negative Light Extensions, or "There are no

1973 ocean streets." 7' 9” x 10' 7” x 14' x 16'.

Tangents of the sun light at 12:30 February 28,

determine shape construction that projects into

building through existing opening jn alley.

On that time and day sun light completely

fills the white construction. Removal by

addition. Viewer walks from street into alley.

1/2 block from ocean.

Plants, with their needs and illnesses, were the privileged objects of all study that took place in this school. This daily and prolong exposure to beings that were initially so far away from me left a permanent mark on my perspective of the world. This book is the attempt to revive the ideas produced by those five years spent contemplating their nature, their silence, and their apparent indifference to everything we call “culture.”

“the standard evolutionary literature is zoocentric.” And biology manuals approach plants “in bad faith,” “as decorations on the tree of life, rather than as the forms that have allowed the tree itself to survive and grow.”

The problem is not just one of epistemological deficiency: “as animals, we identify much more immediately with other animals than with plants.” In this spirit, scientists, radical ecology, and civil society have fought for decades for the liberation of animals; and affirming the separation between human and animal (the anthropological machine of which philosophy speaks) has become commonplace in the intellectual world. By contrast, it seems that no one ever wanted to question the superiority of animal life over plant life and the rights of life and death of the former over those of the latter. A form of life without personality and without dignity, it does not seem to deserve any spontaneous empathy, or the exercise of a moralism that higher living beings are capable of eliciting. Our animal chauvinism refuses to go beyond “an animal language that does not lend itself to a relation to plant truth.” In a sense, antispecies animalism is just another form of anthropocentrism and a kind of internalized Darwinism: it extends human narcissism to the animal realm.

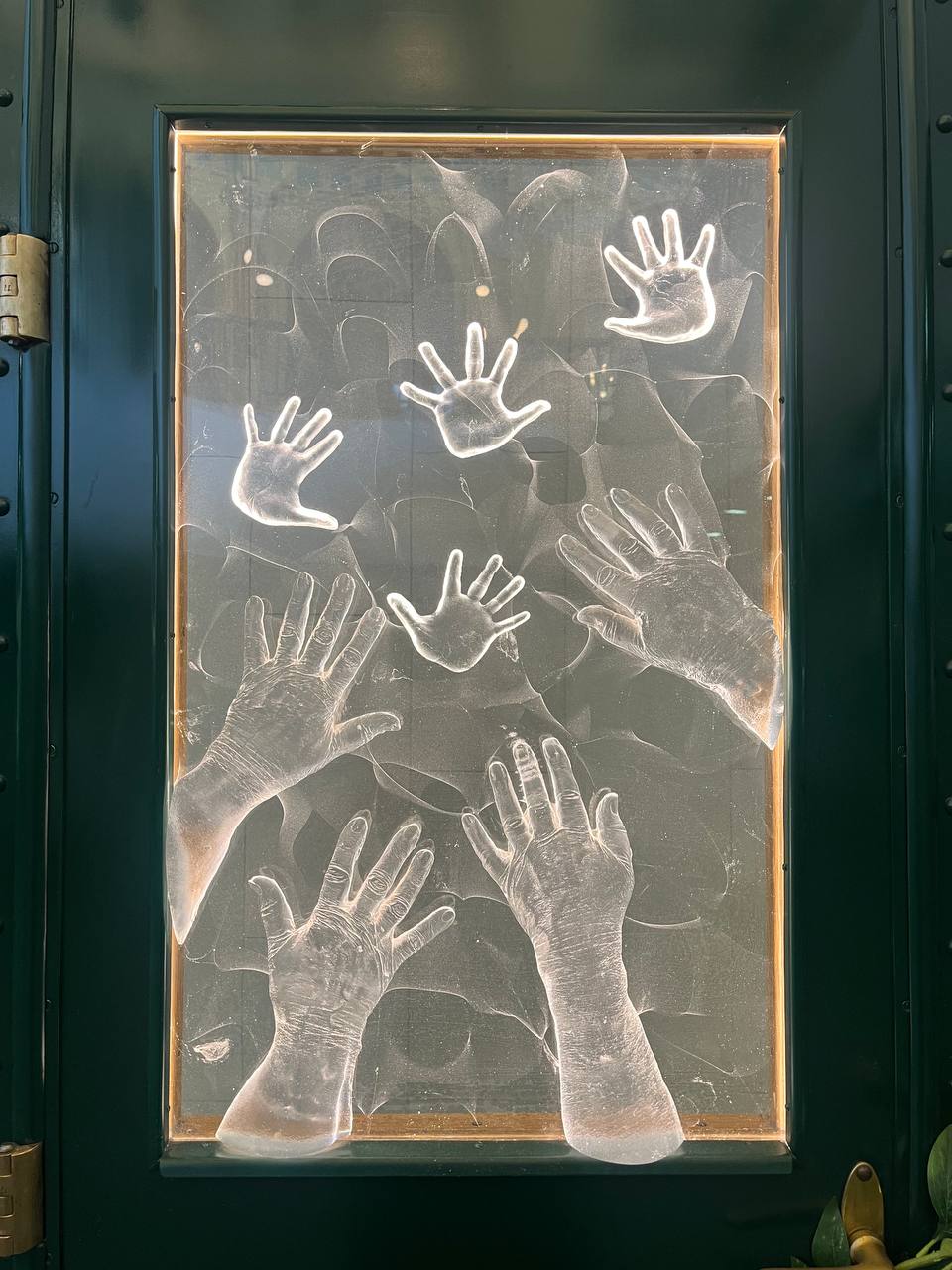

Unlike most higher animals, they have no selective relation to what surrounds them: they are, and cannot be other than, constantly exposed to the world around them. Plant life is life as complete exposure, in absolute continuity and total communion with the environment. It is for the sake of adhering as much as possible to the world that they develop a body that privileges surface over volume: “In plants, the very high proportion of surface to volume is one of the most characteristic traits. It is through this vast surface, literally spread in the environment, that plants absorb from the space the diffuse resources that are necessary to their growth.”Their absence of movement is nothing but the reverse of their complete adhesion to what happens to them and their environment. One cannot separate the plant—neither physically nor metaphysically—from the world that accommodates it. It is the most intense, radical, and paradigmatic form of being in the world. To interrogate plants means to understand what it means to be in the world. Plants embody the most direct and elementary connection that life can establish with the world. The opposite is equally true: the plant is the purest observer when it comes to contemplating the world in its totality. Under the sun or under the clouds, mixing with water and wind, their life is an endless cosmic contemplation, one that does not distinguish between objects and substances—or, put differently, one that accepts all their nuances to the point of melting with the world, to the point of coinciding with its very substance. We will never be able to understand a plant unless we have understood what the world is.

They see the world before it gets inhabited by forms of higher life; they see the real in its most ancestral forms. Or rather they find life where no other organism reaches it. They transform everything they touch into life, they make out of matter, air, and sunlight what, for the rest of the living will be a space of habitation, a world. Autotrophy—the name given to this Midas-like power of nutrition, the one that allows plants to transform into nourishment everything they touch and everything there is—is not just a radical form of alimentary autonomy; it is above all the capacity that plants have to transform the solar energy dispersed into the universe into a living body, [to transform] the deformed, disparate matter of the world into a coherent, well-ordered, and unified reality.

“the animal organism is constructed entirely and simply from the organic substances produced by plants,”

All the objects and tools that surround us come from plants (nourishment, furniture, clothes, fuel, medicine). Most importantly, the entire higher animal life (which has an aerobic nature) feeds off the organic exchange of gases between these beings (oxygen). Our world is a world of plants before it is a world of animals.

life starts by defining itself as circulation of living beings and, because of this, constitutes itself in dissemination of forms

what contains us, the air, becomes contained in us; and, conversely, what was contained in us becomes what contains us. To breathe means to be immersed in a medium that penetrates us with the same intensity as we penetrate it. Plants have transformed the world into the reality of breath, and it is starting from this topological structure, which life has given to the cosmos, that I will attempt to describe, in this book, the notion of “world.”

plants never cease to develop and grow, to construct new organs and new parts of their own body (leaves, flowers, parts of the trunk, etc.), which they previously lacked or had gotten rid of. Their body is a morphogenetic industry that knows no interruption. Plant life is nothing but the cosmic alembic of universal metamorphosis, the power that allows any form to be born (to constitute itself from individuals with different forms), to develop (to modify its form over time), to reproduce, thus differentiating itself (to multiply what exists, provided that it modifies it), and to die (to allow difference to overtake identity). The plant is nothing if not a transducer, one that transforms the biological fact of the living being into an aesthetic problem and makes of these problems a question of life and death.

The seed is only the site in which form is not a content of the world but the being of the world, its form of life. Reason is a seed because, contrary to what modernity has insisted on believing, it is not the space of sterile contemplation, not the space of the intentional existence of forms, but the force that makes it possible for an image to exist as the specific destiny of a given individual. Reason is what allows an image to become destiny, a space of total life, a spatiotemporal horizon. It is cosmic necessity, not individual whim.